William, Duke of Normandy, Lands at Pevensey

- 28th September 1066 -

In history certain ‘inevitabilities’ are fashioned from events that happened some time ago due to the vagaries of hindsight and knowledge. William’s conquering of England and victory at Hastings, so famous, seems to many onlookers as also so inevitable. This episode is far from the case. As many school pupils will tell you William won due in large measure to the luck that he enjoyed.

Back in 1064 King Edward the Confessor sent his brother-in-law and most powerful noble, Harold Godwinson, to Normandy to inform William that he would be the next King of England. William had greatly helped Edward regain his throne and keep him there. Harold, having set out from near Bosham church, made this promise to William on the holy bones of saints in a cathedral. Whether Harold did this against his will is not certain but it seems he did make that promise to William. Whilst in Normandy Harold also helped William fight off rebels such as Duke Conan and capture various castles such as Dinan. For his pains William knighted Harold on the battlefield. Little did the two know that in less than 2 years’ time they would be fighting each other as bitter enemies for the throne of England.

On 5th January 1066 Edward the Confessor died. It is said that he entrusted the Kingdom to Harold and his wife, Edith, Edward’s sister, on his death bed. He was buried in the recently complete Westminster Abbey the following day, the same day that Harold had himself crowned King. The unseemly rush to be crowned, after a vote by the Witan to elect Harold, Earl of Wessex, as the new King, must have been in some measure due to the knowledge that William would come and claim the title. News of the coronation enraged William and he immediately set about ordering an invasion fleet to win back what he felt was rightfully his.

To carry over 7,000 men, horses, armour, provisions, ‘back room’ staff (armourers, carpenters, cooks, fletchers, blacksmiths etc.) would require a huge amount of money and time. William didn’t have nearly enough men in Normandy to carry out such a huge mission and mercenaries would need to be hired from all parts of France and other areas in Europe too. This was expensive and he nearly broke the bank in his efforts to defeat Harold. One of the very important acts that William carried out was to get the blessing and backing of the Pope, Alexander II. This invasion was a crusade against a man who had given his word on holy relics and broken it. This was vital in helping acquire so many men. Without this support it is highly unlikely the invasion would have gone ahead.

To carry over 7,000 men, horses, armour, provisions, ‘back room’ staff (armourers, carpenters, cooks, fletchers, blacksmiths etc.) would require a huge amount of money and time. William didn’t have nearly enough men in Normandy to carry out such a huge mission and mercenaries would need to be hired from all parts of France and other areas in Europe too. This was expensive and he nearly broke the bank in his efforts to defeat Harold. One of the very important acts that William carried out was to get the blessing and backing of the Pope, Alexander II. This invasion was a crusade against a man who had given his word on holy relics and broken it. This was vital in helping acquire so many men. Without this support it is highly unlikely the invasion would have gone ahead.

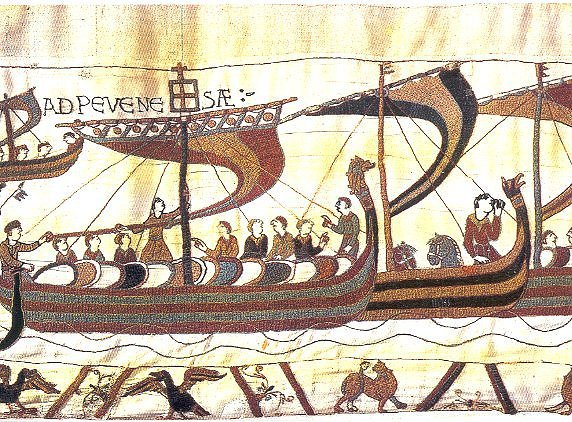

Having received this blessing William brilliantly convinced enough of the aristocracy of Europe to supply him with men. Not only did he ask them for manpower but he also said that they would need to provide the boats to transport those men across the channel. The Tapestry clearly shows a massive boat building programme being undertaken at the start of 1066. The boats were of Viking design, hardly a surprise given that the Normans were direct descendants (North Men -> Norman). The number of boats he used is very hard to calculate. The chronicles give us various numbers and if you work out the army he had, plus the extras, you can also work out how many ships were needed. The numbers vary from a low of 500 up to 776, with the real number probably being in the lower end of that scale. Whatever the number it was an extraordinary feat to prepare for, and carry out, the invasion in nine months. The main suppliers of boats were William’s half-brother, Bishop Odo of Bayeux, the man who commissioned the tapestry, Count Robert of Mortain, stepbrother of William, Count William of Evereux, second cousin of William, Robert of Beaumont, Roger of Montgomery, William Fitz Osbern, Count Robert of Eu, Hugh of Avranches and Hugh of Montfort.

The army itself was divided into three. William’s Normans, that occupied the centre of the battlefield, was comprised of 800-1200 cavalry, 500-800 archers and 2000-2500 foot soldiers. On the left of the army were the Bretons led by Alan Fergant. This had 500-600 cavalry, 300-450 archers and 800-1100 foot soldiers. On the right were the Flemish controlled by Eustace of Boulogne and Fitz Osbern with 300-400 cavalry, 350-450 archers and 700-900 foot soldiers. As well as being reminded of their feudal duties these men had been promised huge riches and power far in excess of anything they already had. Some of the leading lights in the invasion, such as Fitz Osbern became some of the richest people in Britain that have ever lived. The amount of land they were ‘rented’ under the feudal system, that William introduced into England, was vast. Land equalled wealth.

The vast armada and army were assembled at the mouth of the Dives, a river between the Seine and the Orne, in late August. However, an unfavourable wind kept his forces in harbour and there was a real danger that the opportunity to invade would be lost as the risk of a crossing in October would be too great. Whether he would be able to re-assemble his troops the following year would be doubtful. This wind was to prove vital in what was to follow.

The same breeze that kept William in the harbour allowed another invader to attack the coastline of England. Harald Hardrada, King of Norway, also claimed the throne via his Viking lineage. Helped by King Harold Godwinson’s brother, Tostig, who had been exiled for fraud, he had landed near York and defeated a Saxon army led by Earls Edwin and Morcar at Fulford Gate. Godwinson was left in a quandary. His troops were defending the south against the expected invasion of William. If they headed north to take on Hardrada this area would be very exposed.

With the Vikings laying waste to the counties in the north he had no choice and force-marched his army to Stamford Bridge, just outside York. Here he caught the Vikings off guard on September 25th. They were waiting for hostages to be brought to them after the earlier battle and many had no armour or weapons. A third of their army was not even present as they were guarding their ships near Riccall. Even so the Vikings fought with ferocity but were eventually beaten with both Hardrada and Tostig killed.

Godwinson allowed his weary troops to rest but a few days later he received the news he did not want to hear – that William had landed at Pevensey on September 28th and was killing the local people and burning their houses in a strategy to bring Harold to battle before he was ready. It worked. Harold marched back south, picking up new soldiers as he went. Many of his elite army, the housecarls, had been wounded or killed and the local militia, the fyrd, were very inexperienced in the south.

William had used the time in Dives to train and prepare his men but when the winds changed direction he finally set sail on September 27th. His own ship, the Mora, landed first. The ship had a figure head of a brazen child bearing an arrow with a drawn bow. As he dismounted it is said that he slipped and fell. His men thought this a bad sign. With quick thinking he turned to his men, with pebbles in his hands, “See,” he said, “I have England in my hands. It is now mine and what is mine will be yours.” The archers then came off first ready to shoot at the expected resistance. There was none. The rest of the ships beached and were unloaded – men, carpenters, provisions of salted meat, wine, bread, horses, armour.

William used the time wisely around the area where he landed. He built wooden castles – motte and baileys – the first of which was at Pevensey. Then they marched along the shore to a spot near Hastings. He sent out scouts looking for the English army. Eventually they reported back that the Saxon army could be seen. Godwinson was advised to wait for his whole army to arrive but he was impatient to react to what William was doing and the two armies faced each other on the road to London. Harold had occupied a ridge that was to become known as Senlac Hill (blood lake hill) whereas William was in the valley below. Harold’s plan was very different in that he would occupy the ridge and invite the Normans to attack up the hill. His shield wall would be difficult to penetrate by horses or men. Unfortunately, all his archers were still in the north but, he was confident he could hold the ridge and William’s army would become dispirited and the mercenaries would slip away.

The battle took place on October 14th and the outcome is well known. Harold’s inexperienced fyrdmen, thinking they had won after the Bretons retreated, left the safety of the shield wall and the ridge. Eventually the remaining men tired and by dusk the battle was over. The last Saxon King was dead and a new era and way of life for England was to be ushered in.