The Execution of Charles I

- January 30th 1649 -

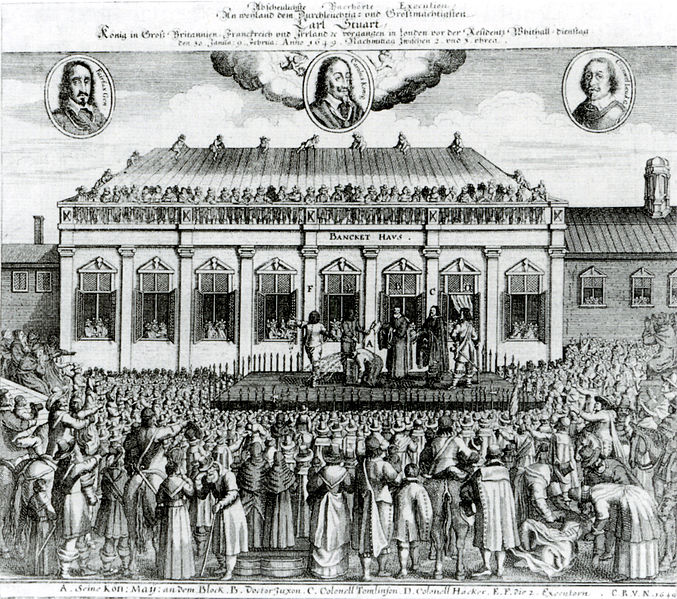

It was a bitterly cold Tuesday, 30th January. A scaffold had been erected in Whitehall. The platform had been covered with a black cloth. A block stood in the middle. This was the block on which Charles I, King of England, was going to be executed for crimes against the people of England; treason.

He had been put on trial on January 1st by the ‘Rump Parliament’, those MPs remaining after Colonel Pride had purged members of the “Long Parliament’ who did not agree with putting the King on trial. The ‘Long Parliament’ consisted of those that refused to dissolve on the orders of Charles. As the Lords refused to sanction the trial the Commons declared itself the supreme authority and a High Court of Justice was convened.

135 commissioners were appointed to sit in judgement of the King. Around 50 of these refused and others withdrew after proceedings had begun. The trial began on the afternoon of January 20th. Security was tight and the President of the court, John Bradshaw, even wore a bulletproof hat. The King, with great dignity and with his long time stutter all but gone, refused to enter a plea as he challenged the authority of the court. How, he asked, could the court claim to represent the people when it had been purged of all dissenters? He refused to answer questions too, as doing so would validate their legality. At the end of each session he was removed by soldiers, which only validated his claim that what they were proposing was far worse than anything he had done.

Witnesses were called against the King and these were heard by a sub-committee and read out to the full court the following day. On 26th a sentence was drafted, condemning Charles Stuart as a “tyrant, murderer and public enemy to the Commonwealth of England.” The following day Bradshaw addressed the court for 40 minutes. He said that even a King was subject to the law and that the law came from Parliament. The bond between King and subject had been broken. He declared that Charles was guilty and delivered the sentence of death. A visibly upset King was not even allowed to speak and was hurried out of the court.

That this conflict should ever have come this far was utterly inconceivable only a year or so before. Compromise seemed likely but try as they might the King could never reconcile himself to the fact that his subjects could tell him what to do and kept breaking any agreement that seemed possible to end the conflict. His certainty and absolute conviction in ‘The Divine Right of Kings’, that meant he was chosen by God and that therefore no one could tell him what to do, was the stumbling block to a lasting solution.

The main cause of the war lay in the different beliefs that Parliament felt they had the right to rule having been put there by the people of England whereas the King did not. His strong Catholic beliefs, his Catholic wife, his disregard for calling Parliament (he had refused to call them for 11 years) and the ways in which he raised money, using old laws such as ship tax, further exacerbated the problem. However it was his arrogance and intransigence that led to war. On Tuesday 4th January 1642, the King had entered the House of Commons with a large number of soldiers to arrest five members he held responsible for the most recent trouble. The Commons would not grant him money to raise an army to fight the Scots, who were rebelling over the introduction of what they saw as a Catholic prayer book. John Pym, John Hampden, Denzil Holles, Arthur Hazelrig and William Strode (Oliver Cromwell was not one of these five as is often thought) had been tipped off and had already left. Charles, sitting in the Speaker’s chair, commented, “I see the birds have flown.” The Speaker, William Lenthall, fell to his knees and replied, “May it please your majesty, I have neither eyes to see nor tongue to speak in this place but as the House is pleased to direct me, whose servant I am here”.

By entering the Commons Charles had broken the sanctity of that chamber and the unwritten rule that the monarch has no right to enter. This is still acted out at the formal opening of Parliament today when the Gentleman Usher of the Black Rod, the representative of the Monarch, walks through the central lobby of the Palace of Westminster towards the chamber of the Commons. As he nears the entrance the doors are slammed shut and he is forced to knock, with his rod, on the doors. At this point the members of the Commons are invited to the Lord’s chamber to hear the monarch’s speech.

This act by Charles led to armies forming and the Civil war officially started when the King raised his standard at Nottingham on Saturday August 22nd 1642. The first major battle was fought at Edgehill, near the village of Kineton, the following day. The King had a chance to destroy the Parliamentarian army but his superior cavalry, led by his cousin, Prince Rupert of the Rhine, rushed off the battlefield to pursue the fleeing troops rather than turn back to finish the job. This had been his chance. By 1643 Oliver Cromwell started to become a key player and he developed the Parliamentarian army, disparagingly nicknamed the roundheads due to their rather severe haircuts. This army was to become known as the New Model Army. It was better equipped, better trained and more disciplined than their opponents. In 1644 at the battle of Marston Moor the King’s army, nicknamed the Cavaliers for their approach, were defeated and the North of England was lost. The decisive battle came at Naseby where the Cavaliers were routed and the army shattered. Charles was never to recover from this.

Even at this point most would have been shocked if they could have seen how events would play out. In 1646 Charles surrendered to the Scots hoping that he could gain their support; his family were, of course, Scottish. However they handed him over to Parliament for £400,000 in January 1647. The problem now was what to do with the King? The captive himself supplied the answer to this question. In November of that year he escaped from Carisbrooke Castle, on the Isle of Wight, and started the war up again with those few followers he could find. This rather short-lived part of the war was soon over after he was defeated at Preston in August 1648. Charles had proved to Parliament that he could not be trusted. The only way to solve the problem was to get rid of him. Sending him to exile would only serve to help him raise a foreign army. Whilst he was alive he would have followers who would try and put him back on the throne.

Thus the trial and sentence took place at Westminster almost as a last resort. On that cold Tuesday morning, January 30th, Charles had been allowed to walk his dog one last time in St James’ Park. His last meal was bread and wine and he wore two heavy shirts so that he did not shiver, as he did not want people to think he was afraid. There was a delay however as the executioner pulled out at the last minute and others refused to do it also. Eventually a man was found, he received £100 and was able to wear a mask so that no one would know who he was.

At 2pm he walked out of the Banqueting House in Whitehall on to the scaffold. Soldiers surrounded it to try and keep the public back. An anonymous witness who saw and heard what happened clearly best describes the next events.

“About ten in the morning the King was brought from St. James's, walking on foot through the park, with a regiment of foot, part before and part behind him, with colours flying, drums beating, his private guard of partizans with some of his gentlemen before and some behind bareheaded, Dr. Juxon next behind him and Col. Thomlinson (who had the charge of him) talking with the King bareheaded, from the Park up the stairs into the gallery and so into the cabinet chamber where he used to lie.

Where he continued at his devotion, refusing to dine, (having before taken the Sacrament) only about an hour before he came forth, he drank a glass of claret wine and ate a piece of bread about twelve at noon. From thence he was accompanied by Dr. Juxon, Col. Thomlinson and other officers formerly appointed to attend him and the private guard of partizans, with musketeers on each side, through the Banqueting house adjoining to which the scaffold was erected between Whitehall Gate and the Gate leading into the gallery from St. James's. The scaffold was hung round with black and the floor covered with black and the Ax and block laid in the middle of the scaffold. There were divers companies of food, and troops of horse placed on the one side of the scaffold towards Kings Street and on the other side towards Charing Cross, and the multitudes of people that came to be spectators, very great. The King being come upon the scaffold, look'd very earnestly upon the block and ask'd Col. Hacker if there were no higher. And then spake thus, directing his speech chiefly to Col. Thomlinson...

...Then turning to the officers, said, "Sirs, excuse me for this same, I have a good cause and I have a gracious God. I will say no more."

Then turning to Colonel Hacker, he said, "take care that they do not put me to pain. And Sir, this, an it please you---" But then a gentleman coming near the Ax, the King said "Take heed of the Ax. Pray take heed of the Ax."

Then the King, speaking to the Executioner said "I shall say but very short prayers, and when I thrust out my hands—"

Then the King called to Dr. Juxon for his night-cap, and having put it on said to the executioner "Does my hair trouble you?" Who desired him to put it all under his cap. Which the King did accordingly, by the help of the executioner and the bishop.

Then the King turning to Dr. Juxom said, "I have a good cause, and a gracious GOD on my side." Dr. Juxon: There is but one stage more. This stage is turbulent and troublesome; it is a short one. But you may consider, it will soon carry you a very great way. It will carry you from Earth to Heaven. And there you shall find a great deal of cordial joy and comfort.

King: I go from a corruptible to an incorruptible crown; where no disturbance can be, no disturbance in the world.

Doctor Juxon: You are exchanged from a temporal to an eternal crown, a good exchange.

The King then said to the Executioner, "Is my hair well?"

Then the King took off his cloak and his George, giving his George to Dr. Juxon, saying, "Remember—." (It is thought for to give it to the Prince.)

Then the King put off his dublet and being in his wastcoat, put his cloak on again. Then looking upon the block, said to the Executioner "You must set it fast." Executioner: It is fast, Sir.

King: It might have been a little higher.

Executioner: It can be no higher, Sir.

King: When I put out my hands this way (Stretching them out) then— After having said two or three words, as he stood, to himself with hands and eyes lift up.

Immediately stooping down laid his neck on the block and then the executioner again putting his hair under his cap, the King said, "Stay for the sign." (Thinking he had been going to strike)

Executioner: Yes, I will, an it please your Majesty.

And after a very little pause, the King stretching forth his hands, the executioner at one blow severed his head from his body. When the Kings head was cut off, the executioner held it up and shewed it to the spectators. And his body was put in a coffin covered with black velvet for that purpose. The Kings body now lies in his lodging chamber at Whitehall.

Another witness describes a great groan in the crowd. After paying a fee spectators were then allowed to come on to the scaffold and dip their handkerchiefs in the blood that was on the staging. The blood of a King was said to be able to cure illness and disease.

The head was re-attached to the body which was now embalmed and laid to rest in the tomb of Henry VIII and Jane Seymour in Windsor.

On February 6th the monarchy was formerly abolished and a council of State established with Cromwell as its first chairman.

Over the course of the next 11 years, called the Commonwealth or Republic, various methods of government were tried from a number of different Commons groups to a military administration with the country divided into areas. In 1653 Cromwell was made Lord Protector after the ‘Rump Parliament’ was formerly dissolved. He was offered the throne but turned it down. After his death in 1658 his son, Richard assumed this title in much the same way a son inherits the throne! However Richard had not the skill or authority of his father and in 1660 the ‘Rump Parliament’ were recalled and they invited Charles’ son to return from the continent to rule as King Charles II in what has become known as the ‘Restoration’. Charles signed the Declaration of Breda, named after the City in the Netherlands, which talked about financial and monetary matters as well as forgiving the enemies of Charles I.

On his return however Charles said that those who had tried his father were exempt from this pardon and that those who had signed the death warrant were regicides. Some were hanged and quartered and the corpses of Oliver Cromwell and John Bradshaw were dug up and hanged in chains at Tyburn. The only man who escaped was the executioner, as no one knew who he was.

It was as if the last eleven years had not happened. Gradually Parliament grew in power again and the constitutional monarchy and representative democracy we have today slowly took shape. The Glorious Revolution of 1688, when William III and Mary II became joint monarchs after the overthrow of the Catholic James II, and the Bill of Rights that followed a year later began to formalise arrangements. Something that had started with Magna Carta in 1215 was forming into the style of Government we now know. 800 years isn’t a bad timescale to form a system of Government. Is it any wonder that some ‘modern’ countries are having a tough time sorting out how best to run theirs?