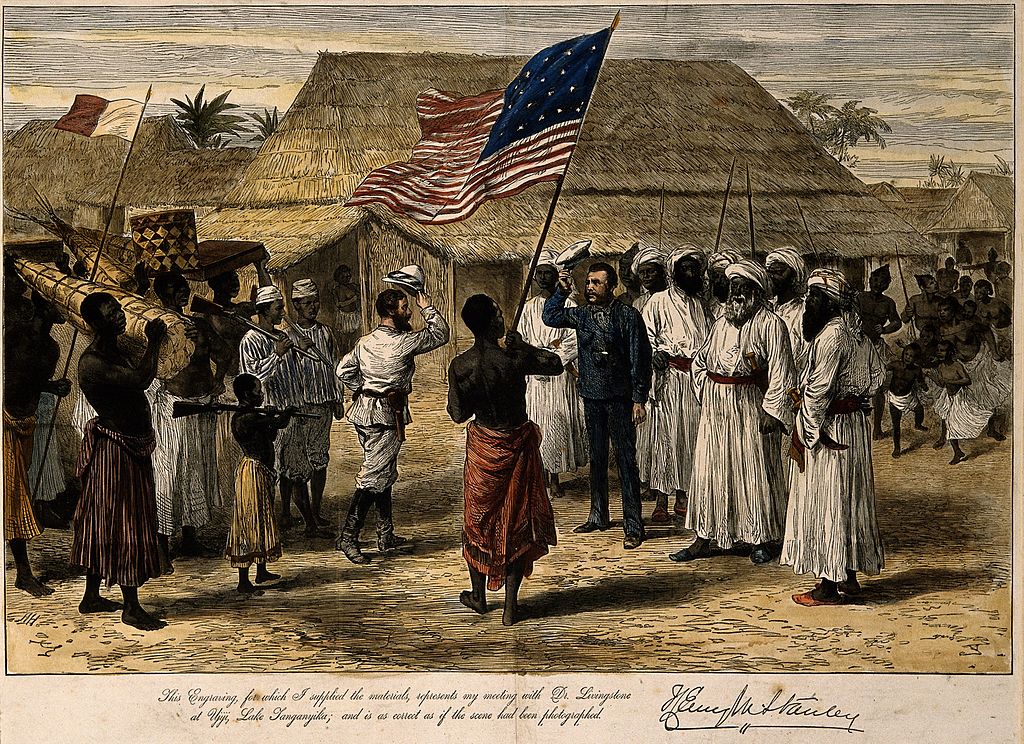

Dr. David Livingstone meets Henry Morton Stanley

- 10th November 1871 – Modern day Tanzania -

I did not know how he would receive me; so I did what cowardice and false pride suggested was the best thing, - walked deliberately to him, took off my hat, and said, 'Dr. Livingstone, I presume?'

I did not know how he would receive me; so I did what cowardice and false pride suggested was the best thing, - walked deliberately to him, took off my hat, and said, 'Dr. Livingstone, I presume?'

'Yes,' said he, with a kind smile, lifting his cap slightly.

I replace my hat on my head and he puts on his cap, and we both grasp hands, and I then say aloud, 'I thank God, Doctor, I have been permitted to see you.'

He answered, 'I feel thankful that I am here to welcome you.'

These were Stanley’s words to Doctor Livingstone when they met on the shores of Lake Tanganyika, told by Stanley himself. The doctor had set of in August 1865 to find the source of the River Nile. This was the Holy Grail for explorers and had been sought since the days of Herodotus in 460BC. The expedition was supposed to last for two years but after six nothing had been heard of the great man. Explorers enjoyed the sort of fame now accorded to film/pop stars or footballers. Livingstone was the Tom Cruise, Jonny Depp or Ronaldo of his day. He was mobbed in the street wherever he went. In 1841 he had walked across the Kalahari desert and traced the path of the 2,200 mile long River Zambezi. In 1854-56 he had journeyed from one side of the African continent to the other. He had also used his fame to preach for the abolition of the slave trade. However his finances had been ravaged by a failed expedition up the Zambezi in 1858-65, which he had been asked to undertake by the Government. He had been ordered home, as his bosses were unimpressed with the results.

He needed one great last adventure and subsequent best selling book. In 1864 Sir Roderick Murchison, Head of the Royal Geographical Society asked Livingstone, aged 51, to try and find the mythical source of the Nile. He readily accepted and took with him 2 servants from a previous expedition, freed slaves, 12 Sepoys (Indian soldiers), Comoros Islanders and Chuma and Sisi – two men who had become family to Livingstone. Chuma was freed from slavery when a boy by Livingstone and both he and Susi had been on previous expeditions with the doctor. It was these two who, when Livingstone died in 1873 of malria and dysentery, carried his body all the way from the village of Chitambo, in modern day Tanzania to Bagamoyo, on the coast of modern Tanzania and delivered him to the British Government so that he could be taken back to London to be buried. They had already removed his heart and buried it under a tree near the spot where he died.

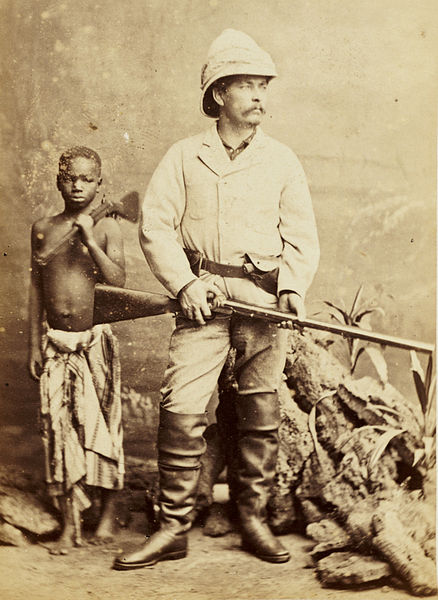

By October 1869 nothing had been heard from Livingstone for a long time. There were rumours that he had been captured, was lost, been killed or had died of illness. There were newspapers headlines asking, “Where is Livingstone?” This story has reached the east coast of America and James Gordon Bennett Jnr, the anti-British 28 year old editor of the New York Herald decided that the U.S. would do something that the British seemed apathetic about doing – namely find Livingstone, or at least find conclusive proof that he had died. From a hotel room in Paris he ordered the young reporter, Henry Morton Stanley, into Africa to find him.

Stanley had a fascinating background. Born John Rowlands in Denbigh in January 1841, his mother abandoned him as a baby and his father died a few weeks after his birth, although the true identity of his father is not definitively known. His mother had many children by different fathers. Whoever he was Stanley never met him. His birth certificate read, “Bastard and stigma of illegitimacy” - something that stayed with him and preyed on his mind for the rest of his life.

He was brought up by his maternal grandfather, Moses Parry, a butcher, but he died when Stanley was just 5. He was then sent to St. Asaph’s Union Workhouse for the poor. Workhouses were places that people were sent to if they were unable to support themselves and offered accommodation and employment. Life was meant to be hard, uncomfortable and brutal to discourage anyone but the most needy. This particular workhouse was overcrowded and there was a lack of supervision. It is reported that Stanley was abused by the older boys and possibly raped by the Head. He stayed there until the age of 15 when he was employed as a pupil teacher in a National School. These particular schools were set up in the nineteenth century and would be the equivalent of faith schools today.

Determined to do better he left and got a job on a merchant ship bound for America. He jumped ship at New Orleans and whilst walking through a pleasant suburb of the town passed a man on his veranda. “Do you want a boy?” he asked the man in a question bathed in English overtones. The character was himself a wealthy trader named Henry Hope Stanley. The latter had never had never had children but had always wanted them and replied that he did. He was taken in and never looked back, even taking the man’s name out of the respect he had for him.

Determined to do better he left and got a job on a merchant ship bound for America. He jumped ship at New Orleans and whilst walking through a pleasant suburb of the town passed a man on his veranda. “Do you want a boy?” he asked the man in a question bathed in English overtones. The character was himself a wealthy trader named Henry Hope Stanley. The latter had never had never had children but had always wanted them and replied that he did. He was taken in and never looked back, even taking the man’s name out of the respect he had for him.

Stanley fought in the Civil War for both sides, was a seaman on merchant ships and even in the US Navy before becoming a journalist, ending up at the New York Herald in 1867. It was whilst working here that he was sent to find Livingstone. He had a large caravan of men and headed into the interior of Africa from the Eastern shoreline near Zanzibar on March 21st 1871. During this expedition Stanley had contracted dysentery, malaria and smallpox. It took him eight months to find the doctor in Ujiji, a small village near Lake Tanganyika, which had been his last known port of call, on November 10th. The exact date is not known for sure. Their two accounts vary with Stanley’s recording November 10th whereas Livingstone had it down as between October 24th and 28th. Livingstone was not well and was short of supplies. The men became friends and on his eventual return to the coast Stanley sent him fresh supplies.

In the summer of 1872 Stanley published his book, “How I Found Livingstone”. Below is an extract from that book about the events surrounding his arrival in Ujiji.

“We push on rapidly. We halt at a little brook, then ascend the long slope of a naked ridge, the very last of the myriads we have crossed. We arrive at the summit, travel across, and arrive at its western rim, and Ujiji is below us, embowered in the palms, only five hundred yards from us! At this grand moment we do not think of the hundreds of miles we have marched, of the hundreds of hills that we have ascended and descended, of the many forests we have traversed, of the jungles and thickets that annoyed us, of the fervid salt plains that blistered our feet, of the hot suns that scorched us, nor the dangers and difficulties now happily surmounted. Our hearts and our feelings are with our eyes, as we peer into the palms and try to make out in which hut or house lives the white man with the gray beard we heard about on the Malagarazi.

We are now about three hundred yards from the village of Ujiji, and the crowds are dense about me. Suddenly I hear a voice on my right say, 'Good morning, sir!'

Startled at hearing this greeting in the midst of such a crowd of black people, I turn sharply around in search of the man, and see him at my side, animated and joyous, - a man dressed in a long white shirt, with a turban of American sheeting around his head, and I ask, 'Who the mischief are you?'

'I am Susi, the servant of Dr. Livingstone,' said he, smiling.

'What! Is Dr. Livingstone here?'

'Yes, Sir.'

|

'In this village?' |

'Yes, Sir'

'Are you sure?'

'Sure, sure, Sir. Why, I leave him just now.'

In the meantime the head of the expedition had halted, and Selim said to me: 'I see the Doctor, Sir. Oh, what an old man! He has got a white beard.' My heart beats fast, but I must not let my face betray my emotions, lest it shall detract from the dignity of a white man appearing under such extraordinary circumstances.

So I did that which I thought was most dignified. I pushed back the crowds, and, passing from the rear, walked down a living avenue of people until I came in front of the semicircle of Arabs, in the front of which stood the white man with the gray beard. As I advanced slowly toward him I noticed he was pale, looked wearied, had a gray beard, wore a bluish cap with a faded gold band round it, had on a red-sleeved waistcoat and a pair of gray tweed trousers. I would have run to him, only I was a coward in the presence of such a mob, - would have embraced him, only, he being an Englishman, I did not know how he would receive me; so I did what cowardice and false pride suggested was the best thing, - walked deliberately to him, took off my hat, and said, 'Dr. Livingstone, I presume?'

'Yes,' said he, with a kind smile, lifting his cap slightly.

I replace my hat on my head and he puts on his cap, and we both grasp hands, and I then say aloud, 'I thank God, Doctor, I have been permitted to see you.'

He answered, 'I feel thankful that I am here to welcome you.'

Then, oblivious of the crowds, oblivious of the men who shared with me my dangers, we - Livingstone and I - turn our faces towards his tembe. He points to the veranda or, rather, mud platform, under the broad overhanging eaves; he points to his own particular seat, which I see his age and experience in Africa has suggested, namely, a straw mat, with a goatskin over it, and another skin nailed against the wall to protect his back from contact with the cold mud. I protest against taking this seat, which so much more befits him than me, but the Doctor will not yield: I must take it. . . .

Conversation began. What about? I declare I have forgotten. Oh! We mutually asked questions of one another, such as: 'How did you come here?' and 'Where have you been all this long time? - The world has believed you to be dead.' Yes, that was the way it began; but whatever the Doctor informed me, and that which I communicated to him, I cannot correctly report, for I found myself gazing at him, conning the wonderful man at whose side I now sat in Central Africa. Every hair of his head and beard, every wrinkle of his face, the wanness of his features, and the slightly wearied look he wore, were all imparting intelligence to me, - the knowledge I craved for so much ever since I heard the words, 'Take what you want, but find Livingstone.'

I called 'Kaif-Halek,' or 'How-do-ye-do,' and introduced him to Dr. Livingstone, that he might deliver in person to his master the letter bag he had been intrusted with This was that famous letter bag marked 'November 1, 1870,' which was now delivered into the Doctor's hand 365 days after it left Zanzibar! How long, I wonder, had it remained at Unyanyembe had I not been dispatched into Central Africa in search of the great traveller? The Doctor kept the letter bag on his knees, then presently opened it, looked at the letters contained there, and read one or two of his children's letters, his face in the meantime lighting up. He asked me to tell him the news. 'No, Doctor,' said I, 'read which I am sure you must be impatient to read. ''Ah,' said he, 'I have waited years for letters, and I have been can surely afford to wait a few hours longer. No, tell me the general news. How is the world getting along?' "

Stanley urged Livingstone to return with him to London but the explorer wanted to continue his original mission and died 18 months later. Stanley for his part returned to Africa, as he promised Livingstone he would, to continue the search. However his own reputation was tarnished when he helped King Leopold II of Belgium establish the Congo Free State, run by the Belgians. This encouraged the slave trade. Upon returning to England Stanley resumed British citizenship and served in Parliament but when he died in May 1904, aged 63, he was refused a burial in Westminster Abbey due to his actions in the Congo and tacit support for slave trading. Ironically in a letter to the New York Herald Livingstone had written, “If my disclosures regarding the terrible Ujijian slavery should lead to the suppression of the east Coast slave trade, I shall regard that a greater matter by far than the discovery of all the Nile sources together.”

Livingstone may not have discovered the true source of the Nile. However his letters, reports and books did help build the momentum for the abolition of slavery. He had witnessed 400 Africans being massacred by slavers near Nyangwe, on the banks of the Lualaba River. The reputation of Livingstone as an explorer is much argued over by historians and geographers. The values and intentions of the man much less so.