Dmitri Mendeleev Publishes his Periodic Table - 6th March 1869.

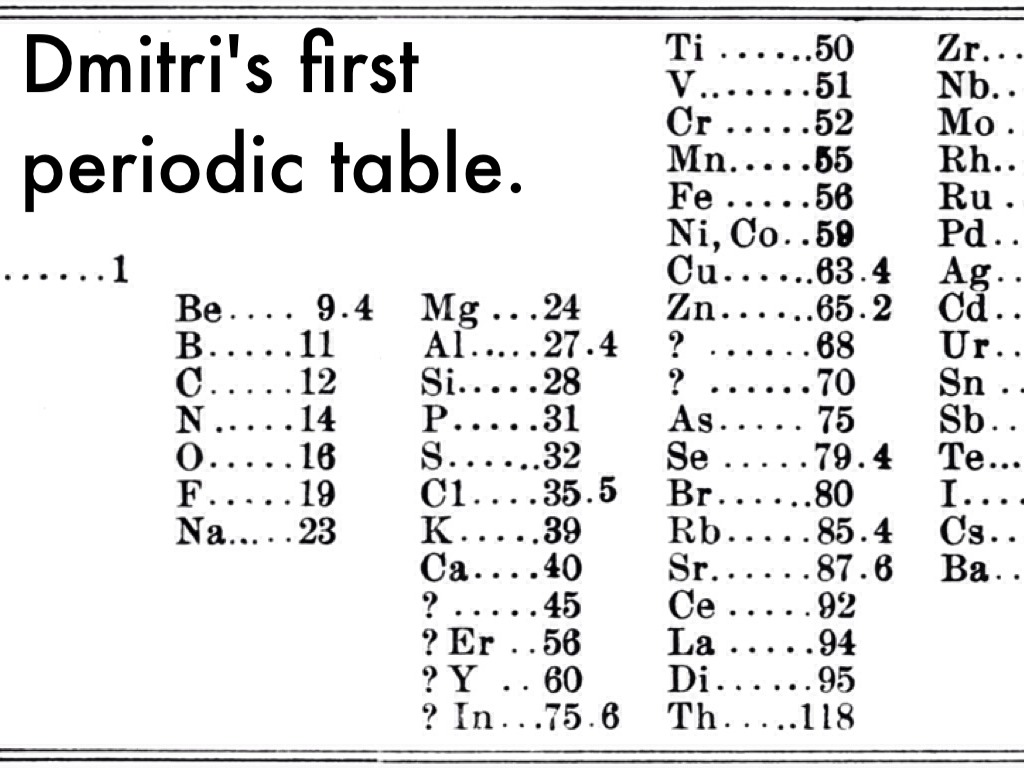

In 1869 Mendeleev published his book, “Principles of Chemistry”. He wanted to simplify the subject and, as far as he was concerned, at the heart of the subject were the elements. He wanted to organise them into groups. Others had tried. John Newlands in 1865 for example. He wrote the 60 discovered elements down on separate cards and played around with them on his table. After a long while he fell asleep but when he woke he claimed that, “In a dream I saw a table where all elements fell into place as required.” He wrote these down and two weeks later he published a second book, ‘The Relation between the properties and Atomic Weights of the Elements’. The periodic table had been born.

What was different about Mendeleev’s table and previous attempts was that he proposed that some of the elements whose behaviour did not agree with his predictions must have had their atomic weights measured wrongly. Secondly he predicted eight new elements as well as their properties. Scientists found out that he was correct in all of those assertions. The weights were wrong and the new elements he predicted were discovered and fitted into his table perfectly. It has been said that what Mendeleev did was like doing a jigsaw puzzle with over 1/3 of the pieces missing and with the other pieces bent.

What was different about Mendeleev’s table and previous attempts was that he proposed that some of the elements whose behaviour did not agree with his predictions must have had their atomic weights measured wrongly. Secondly he predicted eight new elements as well as their properties. Scientists found out that he was correct in all of those assertions. The weights were wrong and the new elements he predicted were discovered and fitted into his table perfectly. It has been said that what Mendeleev did was like doing a jigsaw puzzle with over 1/3 of the pieces missing and with the other pieces bent.

Mendeleev had been born in Siberia as an unusually large baby on February 8th 1834. His father was a teacher of politics and philosophy and his grandfather was a priest in the Russian Orthodox Church. Young Dmitri however was brought up as an orthodox Christian. It is not known exactly how many siblings he had. It is reported as between 11 and 17. It does appear though that he was the youngest of them all. His father became blind and had to relinquish his position and to make money his mother had to re-start the family glass factory. Tragically his father died when he was just 13 and the factory burnt to the ground when he was 15.

His mother then took him to Moscow to try and get him enrolled into the University there. He was refused. She then went to St. Petersburg where he was accepted into the institute at the age of 16. He was the top student in his year. More ill luck was to follow as he contracted tuberculosis and was forced to recuperate on the Crimean Peninsula on the northern coast of the Black Sea. While here he became a science master but returned to St. Petersburg in 1857, fully recovered.

Two years later he was off again, this time to Heidelberg in Germany. It was while he was here that he attended a conference in Germany that was looking at how to standardise chemistry. Here he met Robert Bunsen who, in 1860 had discovered the element Caesium, and went on to develop the Bunsen burner with his assistant Peter Desaga. His ideas were being formed and a year later wrote a book on the spectroscope. By 1864 he had become Professor at St. Petersburg Technological Institute and State University and by 1871 his department had an international reputation for chemistry research.

His personal life meanwhile was in a mess. He had married Feozva Leshcheva in April 1862 but in 1876 fell madly in love with Anna Popova. He threatened suicide if she refused his proposal of marriage and they were married in early 1882. Unfortunately his divorce did not come through until a month after his marriage. The furore surrounding this mess led to his exclusion from the Russian Academy of Sciences.

In 1906 he was put forward for the Nobel Prize in Chemistry for his work on the periodic table by the Chemistry section of this institution. Normally the whole committee of the institute would then rubber-stamp this award. However Henri Moissan was also proposed and the influential Svante Arrhenius, who was not on the Chemistry Committee, complained that the work done by Mendeleev, for which he was proposed for the award, was too long ago to count. He was also upset with Mendeleev for his critique of his dissociation theory. Henri Moissan was voted in. Attempts were made the following year to propose him again but further interference from Arrhenius led to the result turning out the same way.

In 1907 he died in St. Petersburg from influenza. His name though lives on. A crater on the moon is named after him, as is element 101 – Mendelevium. This radioactive element is perhaps a fitting tribute to a remarkable career that as well as directly affecting all those around him, affected the wider world. His periodic table can be found in the countless textbooks and posters that adorn science labs today as well as mugs, bags, pencil cases and t-shirts that show off this piece of work that mixes science with art. It truly is a thing of beauty as well as scientific genius.