The Battle of Balaclava

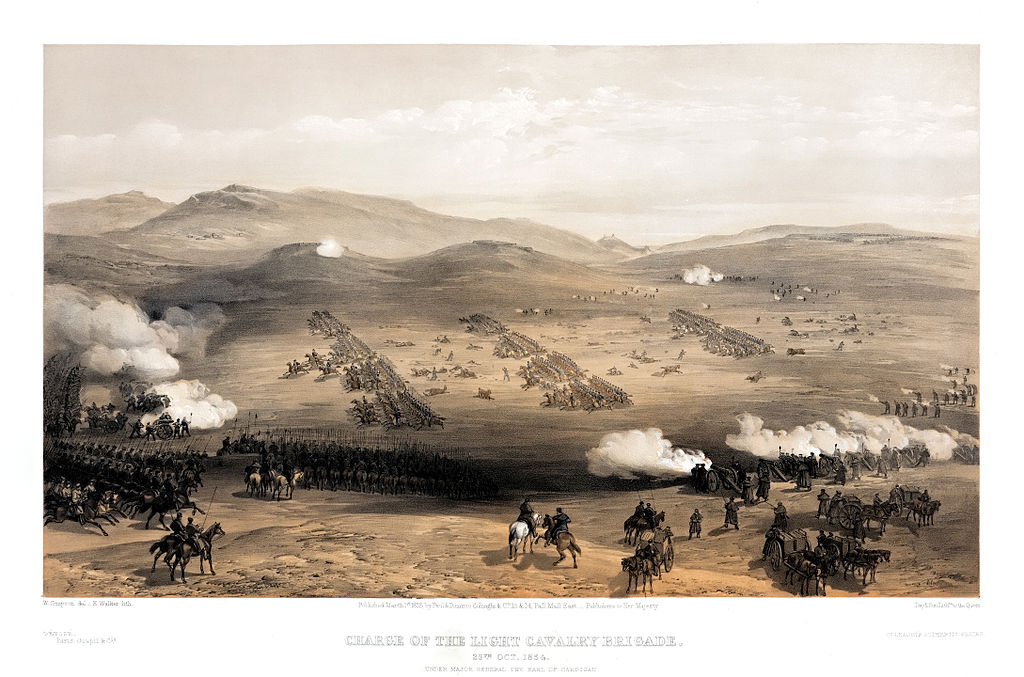

The Charge of the Light Brigade

- October 25th1854 -

The decline of the powerful Ottoman Empire led to a struggle for supremacy between the Russians on the one side and the British and French on the other – supported by the last of the Ottomans themselves. Most of the conflict between these powers took place in Russia’s Crimean peninsular thus giving the war its name.

British and French forces had landed in the Crimea in Mid-September of 1854 and tried to attack the Russian naval base at Sevastopol. They then marched south along the coast where they fought and defeated the Russians at Alma driving them back towards Sevastopol.

Lord Raglan and Marshall St. Arnaud, the two commanders-in-chief, decided to march around the side of Sevastopol and siege it from the south. The French based themselves at Kamiesh on the south-west tip of the Crimea and the English at Balaclava, 15 miles along the coast to the east. The Russian commander, Prince Menshikov, made the decision to march out of Sevastopol leaving a garrison to defend it. This tactic meant that the British and French now had to siege the city and defend itself from attacks from Menshikov who was now getting support from the rest of the Crimea as well as the rest of Russia.

Lord Raglan and Marshall St. Arnaud, the two commanders-in-chief, decided to march around the side of Sevastopol and siege it from the south. The French based themselves at Kamiesh on the south-west tip of the Crimea and the English at Balaclava, 15 miles along the coast to the east. The Russian commander, Prince Menshikov, made the decision to march out of Sevastopol leaving a garrison to defend it. This tactic meant that the British and French now had to siege the city and defend itself from attacks from Menshikov who was now getting support from the rest of the Crimea as well as the rest of Russia.

On 25thOctober the Russian commander led an attack to recapture Balaclava. He had a combined force of 20,000 infantry, 3,500 cavalry and 76 guns. Lord Raglan from his position high up on the SepounéHeights to the west ordered his 2ndand 4thdivisions to march down from their positions sieging Sevastopol to help out. These troops were not happy to carry out these orders. The descent was treacherous, they were exhausted from camping out in trenches and they had already carried out a similar order the previous week – which turned out to be a false alarm.

The Russian army moved towards Balaclava as the Heavy Brigade moved to stop them. From his position Raglan could see the two forces moving towards each other yet neither of the armies themselves could see the other. When the Russians came over the Causeway Heights they saw the Heavy Brigade and stopped. The British charged and after heavy fighting the Russians gave way and fled.

The fleeing Russian headed for the Northern Valley where the British had the chance to finish them off with the other part of their army. This was not taken as Lord Raglan refused to engage despite Captain Morris, one of his deputies, urging him to do so. This refusal has long been the source of much conjecture.

Raglan could also see, from his vantage point, the Russian preparing to remove the guns they had captured from the Turkish. Losing guns was one way of telling how the war was going and he felt he could not allow this to happen. Although he had no infantry he asked for the cavalry to go and stop them. He wrote out the message, “Lord Raglan wishes the cavalry to advance and prevent the enemy carrying away the guns. Immediate.” Captain Lewis Nolan went to give this message to the troops in the area and was met with disbelief. He was asked what guns Raglan meant. He is said to have reacted with outstretched hands and the words, “There is your enemy, there are your guns.”

Lord Cardigan was ordered to charge and after a brief moment of remonstration told his men to mount their horses and he led the charge himself. Raglan, and his staff, watched horrified as the Light Brigade failed to turn up to the Causeway Heights but carried on down the valley into the arms and of the waiting Russian troops. Reaching the end of the valley they plunged headlong into the enemy guns.

William Howard, a correspondent for the London Illustrated News, describes the battle. He was an eye-witness to the events and it is said that his account prompted Alfred Lord Tennyson’s famous poem.

"They swept proudly past, glittering in the morning sun in all the pride and splendor of war. We could hardly believe the evidence of our senses! Surely that handful of men were not going to charge an army in position? Alas! it was but too true - their desperate valor knew no bounds, and far indeed was it removed from its so-called better part - discretion.

They advanced in two lines, quickening their pace as they closed towards the enemy. A more fearful spectacle was never witnessed than by those who, without the power to aid, beheld their heroic countrymen rushing to the arms of death. At the distance of 1200 yards the whole line of the enemy belched forth, from thirty iron mouths, a flood of smoke and flame, through which hissed the deadly balls. Their flight was marked by instant gaps in our ranks, by dead men and horses, by steeds flying wounded or riderless across the plain.

The first line was broken - it was joined by the second, they never halted or checked their speed an instant. With diminished ranks, thinned by those thirty guns, which the Russians had laid with the most deadly accuracy, with a halo of flashing steel above their heads, and with a cheer which was many a noble fellow's death cry, they flew into the smoke of the batteries; but ere they were lost from view, the plain was strewed with their bodies and with the carcasses of horses. They were exposed to an oblique fire from the batteries on the hills on both sides, as wed as to a direct fire of musketry.

Through the clouds of smoke we could see their sabers flashing as they rode up to the guns and dashed between 'them, cutting down the gunners as they stood. . .We saw them riding through the guns, as I have said; to our delight we saw them returning, after breaking through a column of Russian infantry, and scattering them like chaff, when the flank fire of the battery on the hill swept them down, scattered and broken as they were.

Wounded men and dismounted troopers flying towards us told the sad tale. . . .At the very moment when they were about to retreat, an enormous mass of lancers was hurled upon their flank. Colonel Shewell, of the 8th Hussars, saw the danger, and rode his few men straight at them, cutting his way through with fearful loss. The other regiments turned and engaged in a desperate encounter. With courage too great almost for credence, they were breaking their way through the columns which enveloped them, when there took place an act of atrocity without parallel in the modem warfare of civilized nations.

The Russian gunners, when the storm of cavalry passed, returned to their guns. They saw their own cavalry mingled with the troopers who had just ridden over them, and to the eternal disgrace of the Russian name the miscreants poured a murderous volley of grape and canister on the mass of struggling men and horses, mingling friend and foe in one common ruin. It was as much as our Heavy Cavalry Brigade could do to cover the retreat of the miserable remnants of that band of heroes as they returned to the place they had so lately quitted in all the pride of life.

At twenty-five to twelve not a British soldier, except the dead and dying, was left in front of these bloody Muscovite guns."

110 had been killed and a further 161 wounded. In the charge of the Heavy Brigade just 9 were killed. When news reached London there was a national outcry and Tennyson penned this famous poem, which beautifully sums up this disastrous episode in British military history in what must go down as one worst examples of lack of communication and folly.

Half a league, half a league,

Half a league onward,

All in the valley of Death

Rode the six hundred.

"Forward, the Light Brigade!

Charge for the guns!" he said;

Into the valley of Death

Rode the six hundred.

"Forward, the Light Brigade!"

Was there a man dismay'd?

Not tho' the soldier knew

Some one had blunder'd:

Their's not to make reply,

Their's not to reason why,

Their's but to do and die:

Into the valley of Death

Rode the six hundred.

Cannon to right of them,

Cannon to left of them,

Cannon in front of them

Volley'd and thunder'd;

Storm'd at with shot and shell,

Boldly they rode and well,

Into the jaws of Death,

Into the mouth of Hell

Rode the six hundred.

Flash'd all their sabres bare,

Flash'd as they turn'd in air,

Sabring the gunners there,

Charging an army, while

All the world wonder'd:

Plunged in the battery-smoke

Right thro' the line they broke;

Cossack and Russian

Reel'd from the sabre-stroke

Shatter'd and sunder'd.

Then they rode back, but not,

Not the six hundred.

Cannon to right of them,

Cannon to left of them,

Cannon behind them

Volley'd and thunder'd;

Storm'd at with shot and shell,

While horse and hero fell,

They that had fought so well

Came thro' the jaws of Death

Back from the mouth of Hell,

All that was left of them,

Left of six hundred.

When can their glory fade?

O the wild charge they made!

All the world wonder'd.

Honour the charge they made!

Honour the Light Brigade,

Noble six hundred!